Meet the Qualitative Researcher: Una Foye

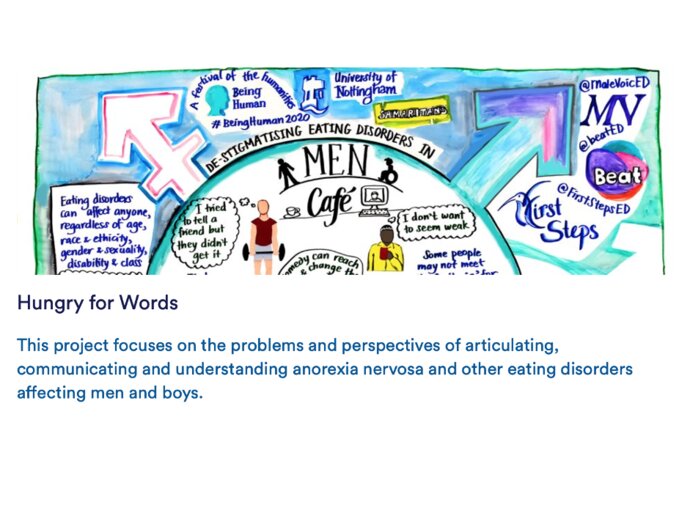

Dr Una Foye is a Research Associate in Mental Health Nursing at the IoPPN. Her work focuses around understanding experiences of living with mental health problems to help improve and develop services. She also is interested in public engagement in mental health, and recently won a Times Higher Education Research Project of the Year (Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences) Hungry for Words, a collaboration between King's and the University of Nottingham aimed at raising GP awareness of eating disorders in men and boys. Here, she reflects on her journey into qualitative research and important things she has learned along the way.

Q: Why do you do qualitative research?

Una: My life in research didn’t begin with qualitative methods. Having done my degree in psychology I was actually a fully fledged SPSS, stats loving quantitative researcher when I started, and had liked the idea of statistics giving you a black and white answer. That all changed when I entered the world of work and began working with individuals with eating disorders, providing support and listening to people; it gave me an appreciation for the complexity and grey parts of the human experience and made me question if statistics can ever capture the nauance of our mental health experiences. Don’t get me wrong, I still love an ANOVA like the best of them and can’t be kept away from a good spreadsheet, but I’ve grown to see the need and exciting side of qualitiatve work in which you get to see the person behind the number. I do qualitative research because it paints colours back onto the human experience and helps see that its never A=B because there's always a hidden C, splash of D, E and F. Also, interviews with people are the best part of research because stats don’t talk back, they don’t laugh or smile, they don’t share themselves, but people do and that’s why I keep doing this type of research.

Q: Tell us about a piece of research you are proud of?

Una: ‘Consider Male Eating Disorders’ was an amazing project I co-lead on with the amazing Prof Heike Bartel from the University of Nottingham. It was work to explore the experiences of men and boys of living with an eating disorder to help build a toolkit and training for healthcare professionals. It used co-production and the output was an amazing animation that used the words and literally the voices of these men who shared themselves with us. There are two reasons this is something I am proud of; firstly because the work received a Times Higher Education Research Project of the Year award which celebrates not only the team and Heike but also recognises the hard work of getting the project endorsed by the Royal College of GPs, RCN, and RCPsychs. Secondly, it a topic that isn’t often seen or acknowledged, and by doing this work it feels like we are able to give a voice to men and boys with eating disorders who are often overlooked.

Q: Whose work have you found helpful or inspiring?

Una: I would say less work but more people that I have found helpful/ inspiring in my qualitative life. I’ve been very lucky to be surrounded by mentors and managers who have been emotionally intelligent and tuned in. Prof Diane Hazlett taught me to listen and be present, Prof Heike Bartel taught me to see beyond words and use creativity and engage with the humanities to see depth, and Prof Alan Simpson taught me its okay to be a person and to bring your human self to the table. All three allowed me to see the importance of lived experience and listening to experts by experience which I have found so helpful in finding my feet as a qualitative researcher.

Q: Most annoying misconception about qualitative research?

Una: That it is the lower cousin of statistics – research undoubtedly has hierarchies which often have Randomised Controlled Trials as the ‘Gold Standard’. Sadly when we have these levels it can mean some methodologies are seem as being lower quality or less valuable; this creates issues with securing funding, publishing in high impact journals, and being accepted in some areas, and that can put early career researchers off doing qualitative work. I think a critical realist epistemology allows a middle ground in this argument meaning that value can be attributed to all methodologies – sometimes we need statistics and outcome based research (e.g. Covid vaccines) but sometimes we need that experiential qualitative work to understand the human experience (e.g. understand accepatance and implementation of healthcare).

Q: What animal/superhero is best at qualitative research?

Una: I look after and walk two dogs called Alfie and Pippy (who I met from Borrow My Doggy) – I think they would be amazing at qualitative research. Aflie is Cavachon who is emotionally intelligent, a great listener who just sits there listening and absorbing the environment, often with payment of a belly rub, which is a sign of a good interviewer. Pippy is a Cockapoo who is so alert, sometimes a little frantic, and always attentitive if anyone moves or speaks, and she can do repetitive things like chasing a ball for hours on end, which would come in handy for coding. (I suspect cats would prefer statistics, and would use things like R and Stata that are too intelligent for me).