Impact in Qualitative Research: Deborah Chinn on the Feeling at Home photovoice project with people with learning disabilities

Deborah Chinn is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Palliative Care and also works as a lead clinical psychologist in the Hackney Integrated Learning Disability Service. She uses qualitative and participatory research methods in her research with people with learning disabilities and is currently leading a project that uses conversation analysis to understand shared decision making in health care with people with learning disabilities.

‘What helps you feel at home where you live? What gets in the way?’ These were the questions that we asked people with learning disabilities who took part in the Feeling at Home research project funded by NIHR School for Social Care Research. As a research team of clinicians, academics and people with lived experience of learning disabilities, we were troubled by the gap between the rhetoric of ‘ordinary lives’, ‘social inclusion’ and ‘person-centred services’ for people with learning disabilities and the very mixed experiences of residents with learning disabilities who live in shared dwellings with staff support. As a clinical psychologist working in an NHS community team, I have visited shared houses that have high end fittings and fixtures, but seem impersonal and run according to staff rules, whereas other dwellings, though more run down, appear to be real homes, shaped by the residents’ personalities and their lively relationships with other residents and the staff.

We realised that ‘feeling at home’ was a concept that was easy for residents, their families and staff teams to relate to. After all, it is not unusual for a sense of relief and belonging to greet us when we come home at the end of a long day. On the other hand most of us at one time or another have not felt at home where we live – the space is wrong for us, or we don’t get on with the people around us.

However, we understood that living with others you are not related to in a shared home run by and staffed by a learning disability provider agency would likely present challenges to generating a feeling of home. The residents’ home is the staff’s workplace and is subject to inspection and regulation. Care needs create their own rhythms and routines. We wanted to find out what ‘feeling at home’ in these settings meant for the residents, their family members and their staff teams, rather than impose our ideas of ‘homeliness’ on them. If residents and staff were struggling to achieve feeling at home could we co-design resources to help nurture this?

We set up three photovoice groups for residents with learning disabilities. All shared their dwellings with others and had substantial staff support. We held the groups in London and Brighton in a community centre, the back of a pub and a disability arts project and each was co-led by a researcher and a person with learning disabilities. Few of our group members had mobile phones so we gave each one a digital camera. We visited the residents in their homes and invited them to take us for a tour and take photographs as they showed us around. We also interviewed staff and family members to understand their perspectives.

The photos that the participants took, how they talked about their homes during the photo taking and within the photovoice groups helped us understand the way how ‘feeling at home’ was realised or undermined. It was dependent on an interplay between material features of the home and its layout, home as a repository and reflection of personal identity and as a site for warm and reciprocal relationships. Feeling at home for the residents was threatened by a sense of precarity – well-loved staff might leave, or the residence might close down - and lack of opportunities to engage in home-making, the domestic and social activities that shape the home environment.

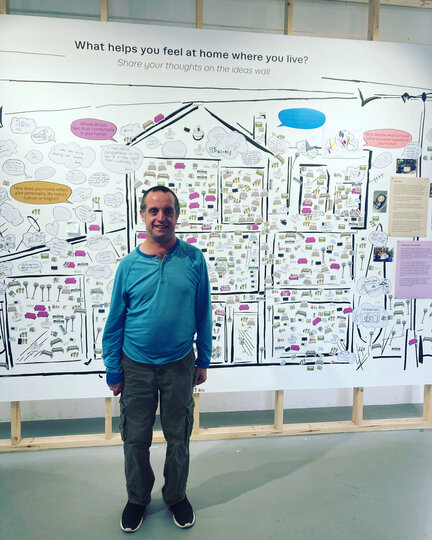

The residents and the research team worked with a Disability Arts Organisation called Quiet Down There to co-curate an exhibition of the residents’ photos. The exhibition was launched at the Phoenix Gallery in Brighton and travelled around the country, to other galleries, including the national photography gallery of Wales and the Science Gallery in London. We engaged the public with our topic through a large interactive sticker wall which invited viewers to reflect on ‘what makes you feel at home?’. Members of the public reported the photos gave them an insight into the ‘hidden lives’ of people with learning disabilities living in their communities and alerted them to overlooked aspects of the social care environment that need to change.

By the end of the project we had produced the Feeling at Home checklist and toolkit; resources for residents with learning disabilities and their staff team to use together to co-create a real sense of home. We had also been convinced by the opportunities presented by the photovoice method. Through photovoice the residents were able to share details of the daily lives with visual representations of its material reality. The photos had travelled far and wide presenting people with learning disabilities as creative practitioners and challenging stereotypes of this group as incapable of representing themselves. We had also created materials for the photovoice group leaders and members, such as an Easy Read guides to using the camera, tips for the group facilitators, documents about photovoice ethics and release and distribution agreements and ideas for putting on exhibitions.

With the input of a King’s Undergraduate Research Fellowship student (thanks Cari Street for a great job!) we decided to develop our photovoice materials into an accessible guide for conducting a photovoice project. We created a series of short videos with accompanying templates for letters, forms and posters. We imagined the guide would be used by community and self-advocacy groups, schools, and students. The guide will be available in the resources section of the Feeling at Home website from next month.

Creating the accessible photovoice guide meant that we were able to realise an aspect of research impact that receives less attention than impact on policy, the public and people who use health and social care services, namely capacity building. The guide is a way of sharing our insights and learning about photovoice with communities who typically have few opportunities to engage with research practices. We hope that other qualitative researchers will take up the challenge to create similar resources!